When it comes to creating a custom eyewear brand, the allure of designing unique, stylish frames that represent your brand’s identity is undeniable. However, as exciting as this process is, diving into customization without a solid understanding of the basic parts of eyeglasses can lead to costly mistakes, unsatisfied customers, and a tarnished brand reputation. Before you embark on the journey of creating custom eyewear, it’s essential to familiarize yourself with the fundamental components of eyeglasses to ensure that your designs are not only aesthetically pleasing but also functional and comfortable.

Understanding Eyeglass Parts: The Foundation of Quality Customization

The key to successful eyewear customization lies in understanding the basic parts of eyeglasses. Knowing the purpose, functionality, and materials used for each component will help you make informed decisions that enhance the comfort, durability, and style of your products. This knowledge is vital whether you’re working with a manufacturer or designing the frames yourself. From the lenses and frame materials to the hinges and nose pads, each element plays a critical role in the overall performance of the glasses. A deep understanding of these components will empower you to create eyewear that not only meets aesthetic expectations but also adheres to quality standards that your customers will appreciate.

Why is This Knowledge Crucial for Your Brand’s Success?

Understanding eyeglass components isn’t just a technical requirement; it’s a strategic advantage. By mastering the details of eyeglass parts, you can communicate more effectively with manufacturers, avoid common design pitfalls, and make choices that will set your brand apart in a competitive market. With this foundation, you’ll be able to innovate while ensuring your products remain practical and reliable.

In this article, we’ve put together a list of the main parts of glasses frames and what they’re really called. Here’s a brief overview.

Glasses frames comprise of three main parts, containing multiple sub-parts within their construction. Primarily, there is the frame-front and two protrusions known as temples. These main components come in many different forms and materials which have their own specific functions, styles and names.

Frame front | Endpieces | Bridge | Lenses | Temples | Temple tips | Hinges | Screws | Nose pads | Rivets | Other parts of glasses

What are the names of the parts of glasses?

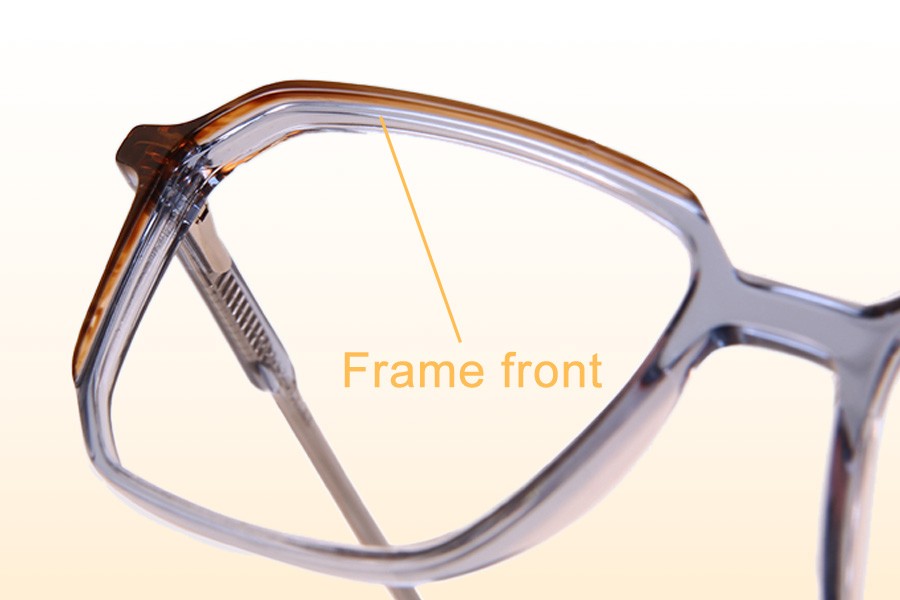

- Frame front

This is the main part of your glasses frame. It’s what secures your lenses in place.

Your frame front largely dictates the style and aesthetic of your glasses, a considerable factor in how you want to put yourself across.

As you’ll have seen, frame fronts vary in terms of their material, colour shape and size. They can be made from various types of material, predominantly cellulose acetate, metal or high-performance composites such as carbon fibre.

Before plastic came on the scene, (1907,) natural materials such as bone, wood, ivory, horn and real tortoise shell were used to make the frame front and temples of a glasses frame. Since then, materials such as cellulose acetate has generally made these older materials obsolete.

Frame front types

Full rim frame fronts cover the entire edge of a lens. Your lenses are held in place using an angled recess in the frame front called a lens groove.

Half rim frame fronts are the same as full rim but their lower half is missing. This means the bottom edges of your lenses are exposed and are secured in place using a thin nylon chord called “Supra.”

Rimless frame fronts are joined together via a metal bridge. Via screws, the bridge joins and secures the lenses together to make the frame front. At the edges of the lenses, the temples are also attached via screws through the outer-sides of each lens.

Frame front sub-parts

Bridge | Endpieces | Hinge graves | Hinges | Lenses | Lens groove | Pad bridge | Rivets | Supra

A tortoise acetate frame front with a double rivet cluster on the endpiece.

- Endpieces

At the outermost edges of your frame front, are the glasses endpieces.

This is where the temples locate onto the rear side of the frame front via the hinges. Endpieces vary in size and shape, depending on the style of temples on your glasses.

Endpiece types

Full rim/half rim endpieces usually have recess on their rear-side to accommodate the hinge. This recess is called a hinge grave where the hinge locates into the frame material surface. Depending on the type of hinge, you’ll often see rivets that pass right through the frame front in order to fasten the hinge.

Rimless endpieces are actually part of temple instead of the front. Beyond the hinge is another section of metal called a “lug”, which is usually a bent at an angle of about 96°. The lug is then screwed through the lens to create a firm joint.

Endpiece sub-parts

Rivets | Deco rivet | Hidden hinge | Hinge graves | Hinges | Lenses

Four types of metal glasses bridges. Far right example is a metal keyhole bridge.

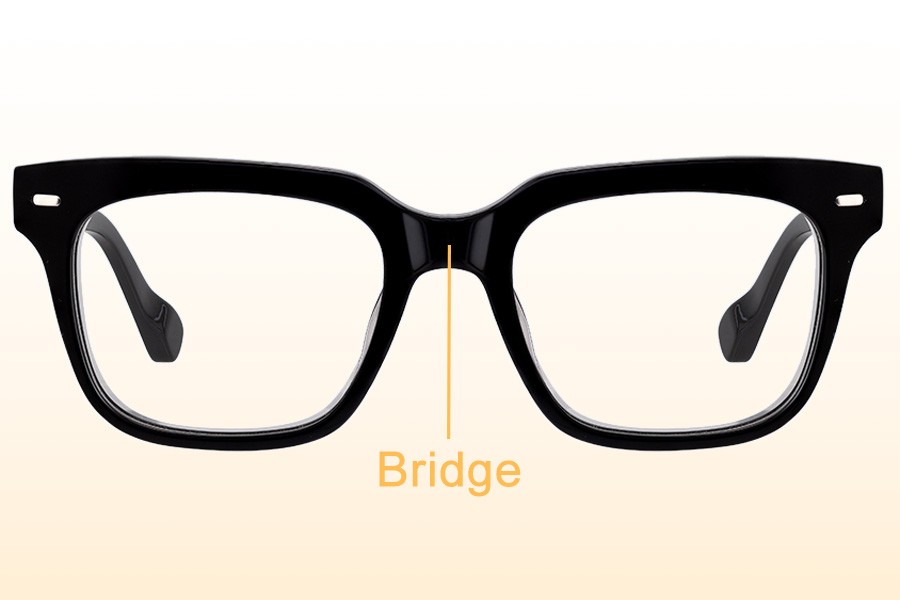

- Bridge

What is the bridge on glasses?

Sounds simple, but your glasses bridge is exactly that. It bridges your nose.

For facial comfort, the bridge of your glasses has two main functions. These come from bridge bump and the bridge aperture.

From above, you’ll notice that the bridge protrudes slightly from your glasses frame. This is called the “bump” which creates room for the crest (top) of your nose as the glasses rest on your face.

The bridge aperture, also called the bridge apical radius, can be seen from the front of the frame. This space makes room for the majority of your nose. Without this space, your nose couldn’t locate into your glasses frame.

Bridge sub-types

Regular bridges are a continuous, flowing shape which make a U-shaped slot in the frame front. This style of bridge is relatively modern and is very simple in appearance.

Keyhole bridges are a traditional style of bridge which resembles that of a keyhole. This bridge-style is generally more classic, associated with full rim eyewear design from the mid-century.

Metal bridges are used for either rimless frame fronts or for acetate “split frames.” For acetate split frames, a conjoining piece of metal is riveted or screwed into the separate acetate rims to join them together.

For rimless frames, it’s very much the same but the bridge is attached with screws through the lenses instead.

Bridge sub-parts

Keyhole bridge | Metal bridge | Nose pads | Pad bridge | Regular bridge

Examples of a concave and a convex lens. These lenses are actually made from glass but most modern lenses are made from CR39 plastic.

- Lenses

Arguably the most important part of your glasses, the lenses are there to correct your vision.

There are many types of spectacle lenses, which were originally made from glass. However nowadays, most if not all spectacle lenses are made from types of high index plastic.

Depending on the type of frame front, your lenses are secured into your gasses using different types of friction fit. The optical term for fitting your lenses is a process called glazing.

Full rim frames have an angled female recess on the inside of the rim called a lens groove. This recess is about 1.5mm deep at an angle 120°. Cut onto the edge of the lens is a ‘male’ bevel which locates into a ‘female’ lens groove by heating and gently stretching the frame front.

Half rim frames also have a lens groove but with the addition of a Supra chord. This nylon string locates into a female recess around the edge of lens which holds it into place in the frame.

Rimless frame lenses are secure via screws into the bridge and endpieces.

Lens sub-types

Bifocal | Prescription reader | Ready reader | Single vision | Varifocal | CR39 | Crown glass | Plano | Polycarbonate | Trivex | Supra

A tortoise acetate example of a hockey-end temple. Dual rivet | 5 tenon hinge | Wire core

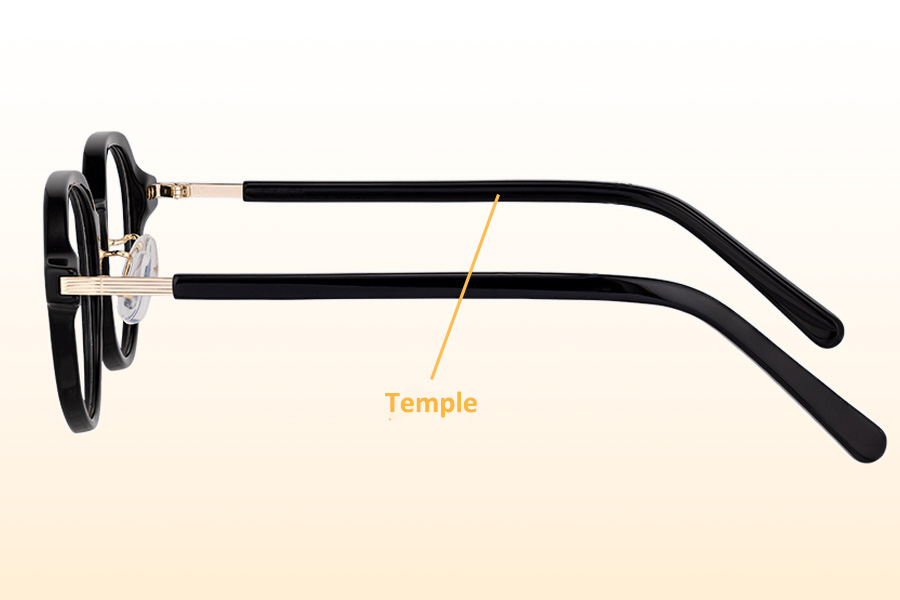

- Temples

What part of glasses is the temple?

Oh boy these parts of glasses have some strange names.

Some call them legs, other call them arms.

Seems logical…but the proper name for them is temples, simply because they locate on each side of your head.

There are numerous styles of temple, but their main function is to keep your glasses secure when you’re wearing them.

Interestingly, temples are actually relatively modern as old-fashioned glasses didn’t originally have them. Instead, these old styles of glasses without temples just rested on your nose or were held to the face via a handle.

Yep, we’re talking templeless glasses here folks like lorgnettes and monocles.

Today, glasses temples tend to be made from acetate or metal and use what’s called a drop end or a hockey end. This is the hooked part of the temple that’s grips behind your ear to keep them from sliding off your face, usually at an angle of about 45°.

Glasses temples are made at various lengths to suit different head sizes and vary from 120mm to 150mm in length.

Wondering what length of temple you need?

This information is usually printed or etched onto the inside of the temple itself or occasionally the inside of the frame front. Alongside the bridge with and lens diameter, the temple length is part of the three main dimensions of a glasses frame.

Do you have a transparent acetate glasses frame?

If so, you might notice a strip of metal inside the temple. This component is called a wire core which is used to reinforce the acetate to help keep its shape.

Without this, your temples would eventually become warped and would require repeated heat adjustments to keep them in the correct shape. The wire core helps maintain adjustments carried out by your optician.

Temple sub-types

Blade temple | Curl sides | Drop end | Hockey end | Paddle temple | Unipiece temple

Temple sub-components

Frame dimensions | Hinges | Hinge graves | Rivets | Wire cores

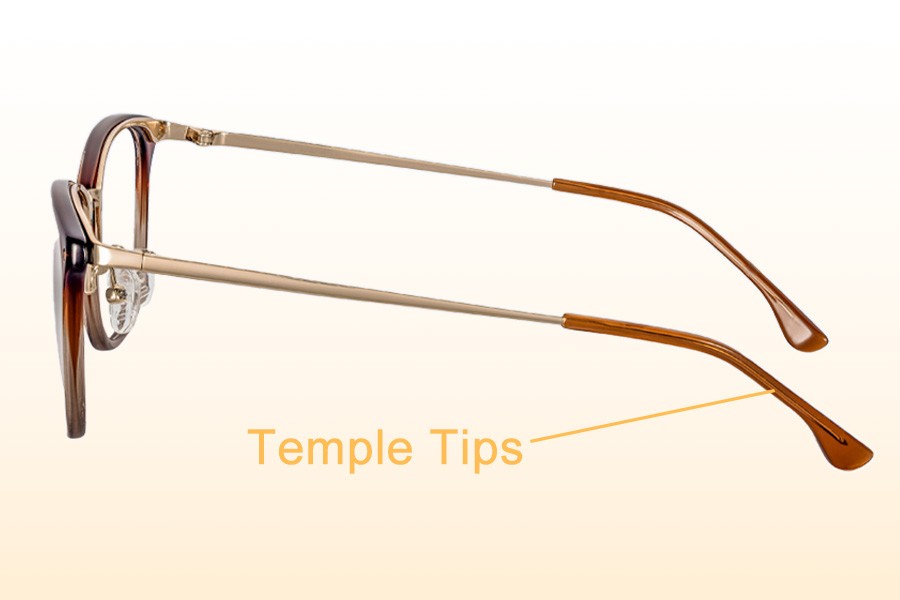

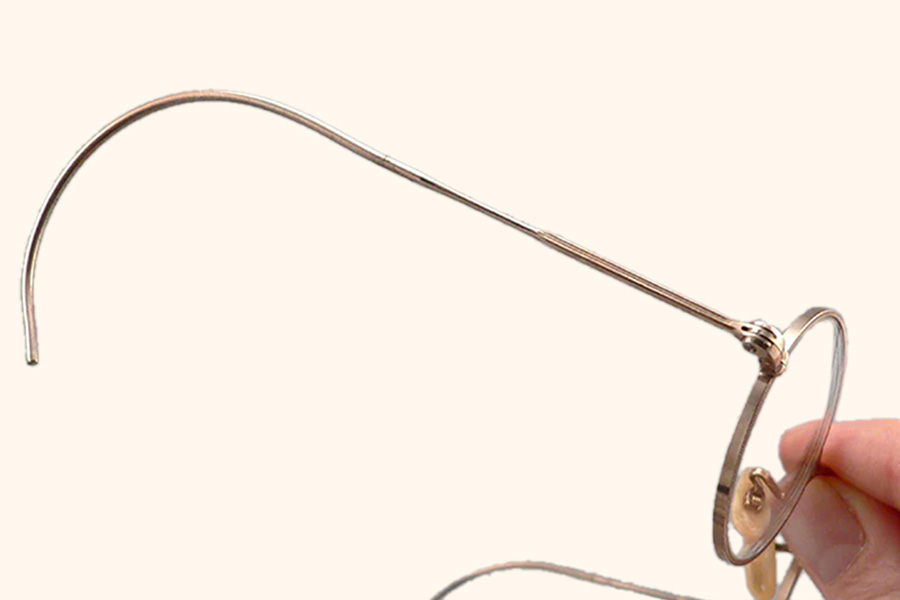

An array of different temple tips made from acetate. These tips slot over the ends of metal temples to provide a comfortable fit behind your ears.

- Temple tips

What are temple tips?

At the end of your temples are the temple tips.

These are the furthest away from your frame and are made in various iterations.

Acetate glasses temple tips are usually part of the temple itself. However, they can also be added to the end of metal temples, similar to a sock. Seen in the images above, there are different colours, patterns and shapes of acetate temple tip which can be added to a metal temple.

Metal temple tips are usually covered or coated with plastic or rubber to make them more comfortable. However, our uni-piece temple design is cylindrical in form and tapered which reduces the need for additional parts and makes them incredibly easy to wear.

Loop end temple tips are hollow loops which can be found at the end of a straight metal wire temple. These loops are to distribute pressure on the sides of your head and can also be used to attach a frame chain.

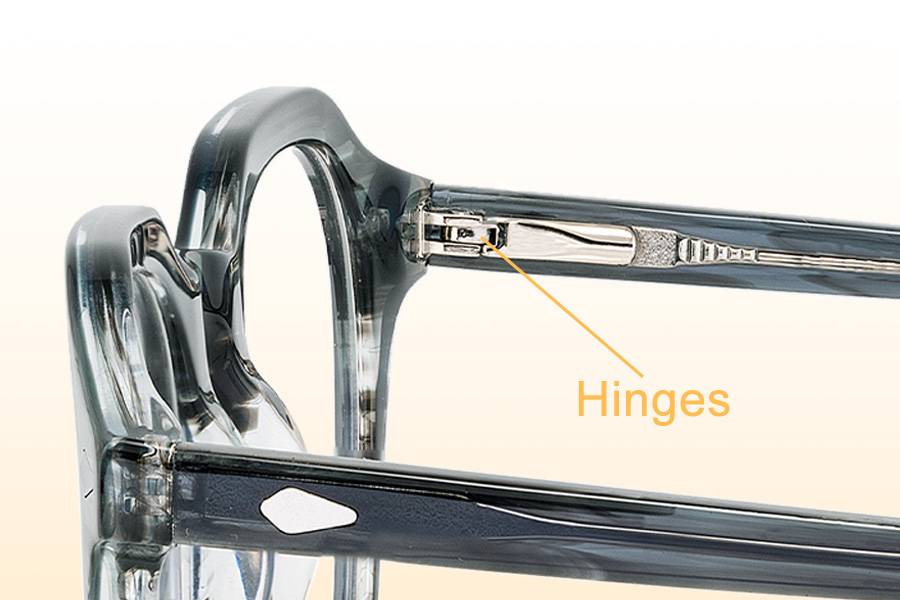

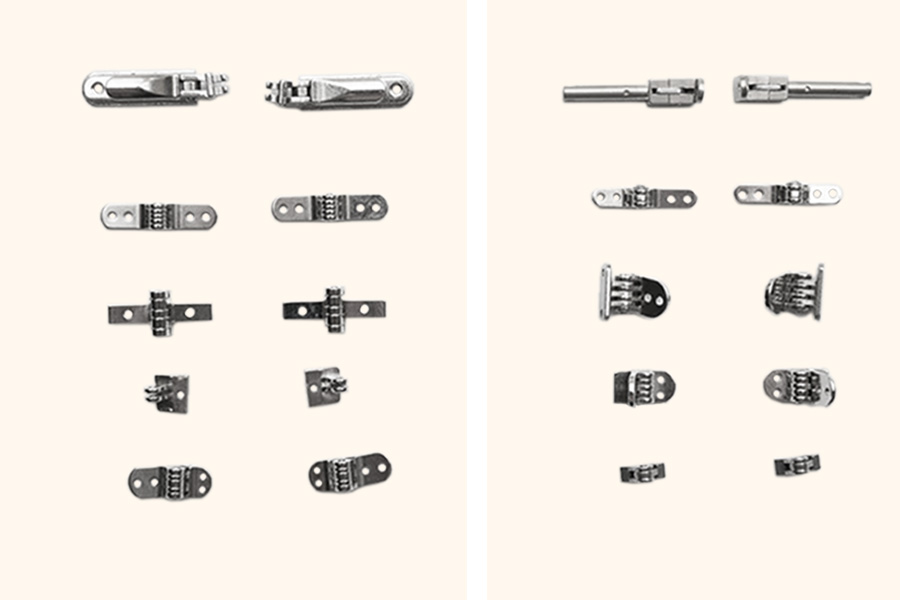

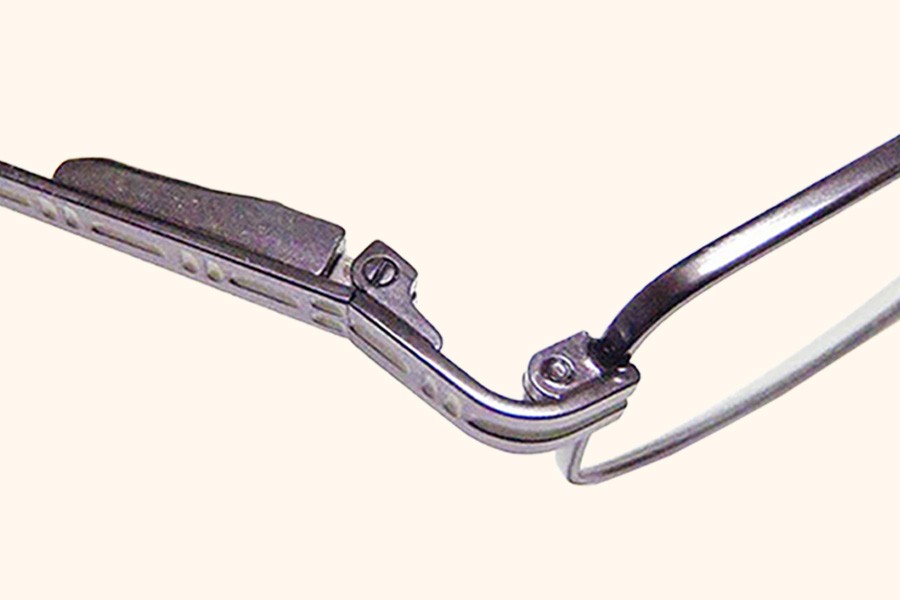

An assortment of metal spectacle hinges which can either be riveted, screwed, melted or soldered into a glasses frame.

- Hinges

Your hinges are the metal joints which allow you to open and close the temples on your glasses frame.

Hinges can also be called “joints” as they conveniently join your frame front with each of your temples.

And yep, you guessed it, there’s many variations of glasses hinges which are secured via many different methods. Check out the list below.

Hinge sub-types

Tenon hinges are an extremely common hinge-type used for solid full rim glasses made from acetate, horn or composite fibre.

The term tenons, also called charniers, describes the threaded metal loops which interlock with each other to join the frame and the temples together. Tenon hinges are a very stable type of hinge and come is different tenon counts such as 3, 5, 7 and 9.

Characteristically, tenon hinges do not have any “give” as they are not sprung. When the temple is fully open and meets the frame, a tenon hinge will no let it open any further; a similar function to a house-door.

If your glasses have a tenon hinges, they will likely be fastened in one of two ways, either via pin rivets or heat-insertion. Pin riveting is the most traditional method of attaching a tenon hinge to a glasses frame as they provide a solid fix between the hinge and the frame front.

Spring hinges are also very common and are used in full rim and rimless glasses frames.

They are characterised by their “give.” In other words, when you fully open the temple, it can extend beyond it’s maximum distance range. This is because of the in-built spring within the hinge, hence the name.

Spring hinges are common amongst low cost glasses frames such as ready readers. They can cater for a wider range of head shapes and offer a one-size-fits-all mechanism.

However, it’s worth noting that spring hinges are generally less stable than tenon hinges due to the internal spring mechanism which is more likely to break.

Hidden hinges are identical to tenon hinges, except they have no additional fasteners such as rivets.

Instead, hidden hinges are inserted into the frame via heat or ultrasonic friction which rapidly melts the acetate surrounding the hinge.

This melt makes a sturdy bond between the hinge and the frame without the need for rivets. As you can imagine, hidden hinges are a sleeker design with less components, however they are very rarely repairable.

Because hidden hinges have no rivets, brands and manufacturers may opt to use deco rivets or dummy rivets which mimic the use of real ones. This is done to yield a more traditional construction aesthetic.

Mechanical hinges are bespoke hinges which use cleverly engineered components to reduce the parts and “bulk” of traditional tenon hinges.

Instead of using screws and tenons, mechanical hinges may use entirely wooden or intricate folded metal parts which avoid the need for pin riveted hinges.

Hinges like these are less common as they tend to be used in high-end, technical glasses frames.

Hinge sub-components & types

Charniers | Tenons | Hidden hinges | Hinges | Hinge graves | Rivets | Dowel screws | Cross head screws

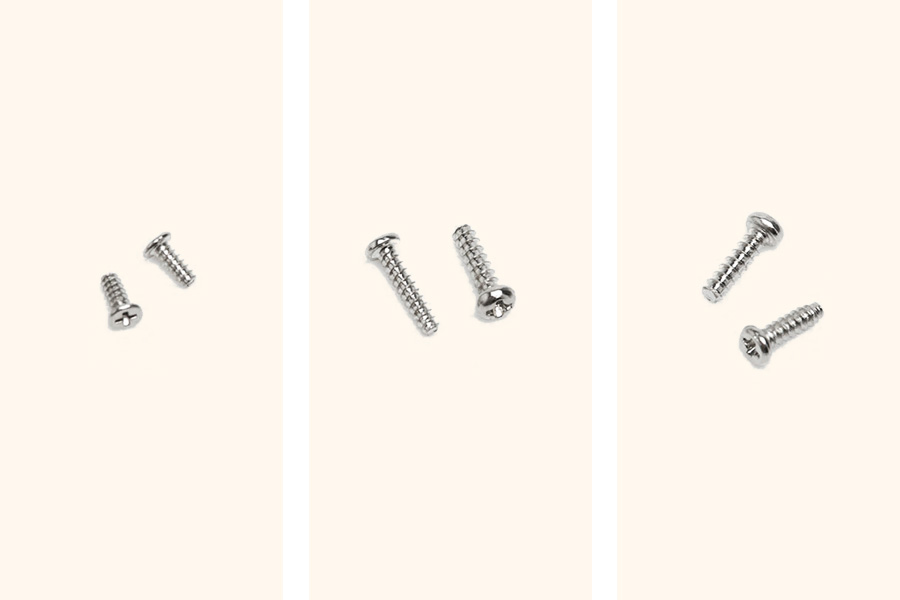

Thread seeking screws have a detachable “nose” which makes them easier to locate into the threaded tenons of a hinge. Screw head: Dowel

- Screws

The screws are what join the two halves of a hinge together.

Using one screw per hinge, the screws locate through the interlocked tenons of your glasses hinges.

Once located, the screws can be tightened to adjust the opening and closing mechanism of your temples. This can be a personal preference as to how tight or loose you want this to be.

If you’ve lost a screw from your glasses frame, you’ll be able to get a replacement from your local optician. Or, if you’re a Banton Frameworks customer, you can request a pair of replacement thread seeking screws by contacting us here.

Screw sub-types

Dowel screws are the most common type of glasses screw. They are characterised by the straight slot in the top of the screw head.

Cross head screws are slightly less common and use a cross shaped (Phillips) slot in the top of the screw head.

Thread seeking screws are a fantastic design which makes it easier for you to locate the screw into the top tenon of the hinge. They do this via an extended metal “nose” which tapers to a fine point. This nose can then be snapped off once the screw is fully tightened into the hinge as it is no longer required.

See also: Dowel screws | Cross head screws | Thread seeking screws | Tenons | Charniers | Hinges

Three examples of hypoallergenic spectacle nose-pads. Silicone and titanium.

- Nose pads

What are the nose pieces on glasses called?

The nose pads of your glasses are the little humps or circular pads that rest on your nose.

Depending on what style of frame front you have, there are various types of nose pads for glasses frames. These can either part of the frame front material or as a separate metal piece called a pad arm.

Nose pad sub-types

Full rim nose pads are almost always part of the frame front. When the frame front is being cut from the acetate or horn sheet, the nose pads are sculpted as part of the frame as a single piece.

Nose pads like these are very robust and can be adjusted by filing the acetate or horn away to reduce their height. To make them smooth again, the nose pads require hand polishing so they aren’t rough on your nose.

Push in nose pads are a secondary item which use a separate glasses part called a pad arm. The pad arms are either inserted into an acetate/horn frame front or attached to a metal front via soldering. Once the pad arm is attached to the frame, a nose pad can be attached to end where it rests on your nose.

Push in nose pads vary in shape, size and material depending on your preference. The bigger the nose pad, the more visible it is. However large nose pads distribute more pressure and are less likely to “dig” into your skin.

Ideally, nose pads should always be hypoallergenic which minimises their chances of reacting with your skin. This is why metal pads are usually titanium and plastic ones are made of rubber or acetate.

See also: Pad arms | Pad bridge

Example 1: Pointed, pan-head rivets | Example 2: Staple rivets | Example 3: Tapered rivets

- Rivets

If your glasses have tenon hinges, they’ll most likely be fastened via two or three little metal rivets.

The rivets are located in a tightly-packed cluster on the frame front endpiece and the outside of the temple near the hinge.

As mentioned previously, the rivets are located through small diameter holes in the frame front and the temple which are used to permanently fasten the hinges.

Using a process called riveting, sometimes called staking, the ends of the rivets are squashed, deformed and widened to squeeze the hinge onto the frame front or the temples.

Depending on the type of hinge, the amount of rivets can vary between a two-cluster and a three-cluster formation which are used equally for the frame and the temple.

- Two-cluster formations means a glasses frame will have 8 rivets in total (four for each side.)

- Three-cluster formations means a glasses frame will have 12 rivets in total.

Rivet sub-types

Pan head rivets look similar to a wood-nail. They have a uniform 1mm shank and a wider, circular flat top which can be seen on the frame front endpiece.

Double rivets have two 1mm shanks which are joined together at the top via a conjoining strip of metal called a cross bar. Rivets like these can be branded or styled as per a company’s branding.

Tapered rivets have a conical shank and don’t have a top. Instead they taper from a wide head down to a narrow tip at the bottom.

Style rivets have a decorative head which can be shaped to resemble a company emblem or certain geometry. These are less common but offer minor degree of differentiation from regular pan head or tapered rivets.

Deco rivets are used on full rim frames to mimic the appearance of actual rivets. Instead of passing through the frame, deco rivets are entirely superficial, added to the surface of a frame which uses hidden hinges.

Related rivet parts

Hinges | Hinge graves | Rivet hole | Rivet head | Rivet shank

Other parts of glasses

If you’ve made it this far, you’ll know by now that there’s A LOT of styles and types when it comes to the various parts of glasses.

In this more detailed section, you can explore the sub-types of each component to get an idea of their shape, style, material and function.

Why not use the link-box below for easy navigation?

Acetate | Charniers | Cross head screws | Curl sides | Dowel screws | Drop end | Hidden hinges | Hinge graves | Hockey end | Joint | Keyhole bridge | Lens groove | Loop ends | Pad arms | Pad bridge | Paddle temple | Regular bridge | Rim | Rimless | Side shields | Spring hinges | Supra chord | Tenons | Windsor rim | Wire cores

Acetate

Acetate glasses frames are made from a type of bio-plastic called cellulose acetate.

This incredible material is a natural compound which derives from the fibres in cotton ‘bolls’ or mashed up wood pulp.

Due to their high levels of cellulose, wood or cotton are both excellent sources which are cultivated, refined and mixed with acetic acid to make the sheet material, cellulose acetate.

Acetate comes in a vast variety of colours, patterns and transparencies which make it one of the best polymers for spectacle making.

An example of a five charnier glasses hinge with a two rivet cluster. The frame half-joint has two charniers and the temple half joint has three charniers.

-

Bulk Buy Acetate Eyeglasses – Vintage 9631

$99.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Bulk Wholesale Acetate Eyeglasses – Vintage 529

$99.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Buy Acetate Eyeglasses In Bulk – Vintage 9543

$99.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Wholesale Acetate Eyeglasses Distributor – Vintage 9632

$99.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Charniers

Sounds fancy. French even.

(It is actually French.)

But the charniers of a glasses hinge are the little protruding loops that interlock with one another to create a fully assembled hinge.

Seen in the image above, each of the charniers have a hole in their centre’s. This is where a threaded screw locates to secure all the loops together. Each half of the fully assembled hinge is called a half joint.

See also: Tenons | Screws | Hinges

Cross head screws

Glasses screws are generally two types.

There are dowel screws and there are cross head screws.

In the images above, you can see the characteristic cross head at the top of each of the screw-heads.

Depending on the hinge-type, glasses screws will vary in length to pass right through the interlocking tenons to hold them all securely together.

See also: Dowel screws | Tenons | Charniers | Hinges

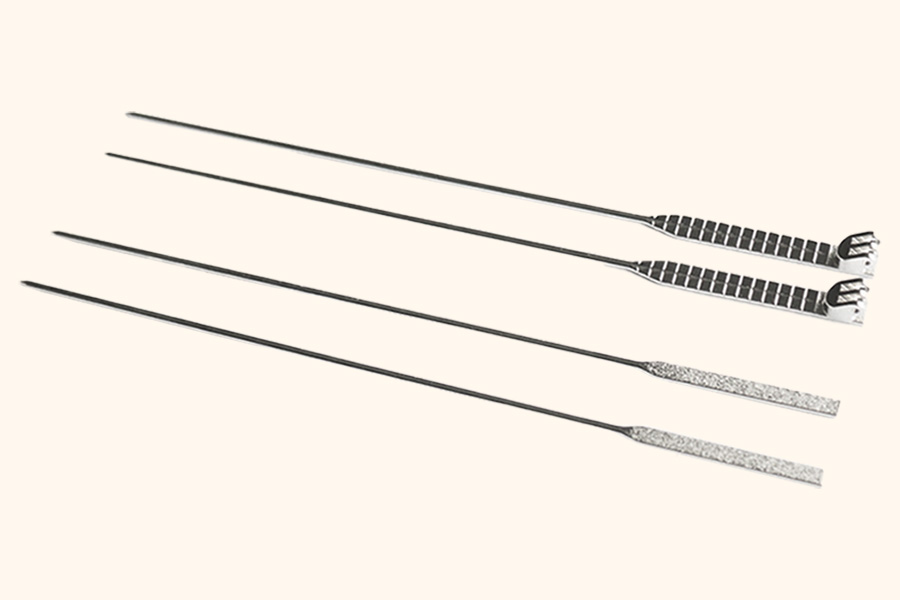

Curl sides

Functional, traditional and oh so snug.

Curl sides do exactly that. They curl behind your ear to give a very secure and snug fit, perfect if you like to keep your frame tight to your face.

Curl sides are more common amongst wire rim frames as the temples tend to be equally fine in thickness. The ends themselves are actually sprung as they’re made of very fine coiled metal, much like a spring.

This temple-style became prominent during the late 1800’s and were popular for more strenuous activities such as horse riding. Wearers benefited from their secure fit around the ear, keeping their glasses frame in perfect place.

Because of their intense grip on your head, curl sides are generally best cut to size for your individual head-dimensions.

See also: Temples | Paddle temple | Drop end | Hockey end

Dowel screws

Also called a “flat head” or “slot screw,” these are an extremely common screw-type.

These little screws are what holds your entire glasses frame together and are arguably one of the most important parts of glasses frames.

In each of your hinges, the dowel screw locates and into each of the threaded tenons. Using a flat-headed screwdriver, the screw is wound tight to pull each half joint together to create a firm and durable connection.

Over time, dowel screws may work loose, so it’s always handy to have an optical screwdriver to keep them tight, but not too tight.

Over-tightening your glasses screws may damage the fine threads, either in the hinge tenons or on the screw shank. Take care to avoid this.

You heard it here.

See also: Cross head screws | Tenons | Charniers | Hinges

Drop end

In modern eyewear, glasses temples generally use what’s called a “drop end”.

The “drop” happens in the last portion of the temple where it hooks downward to create a secure fit behind your ears. Drop ends can also be called “hockey end” or “swan neck” for obvious reasons.

Temples without a drop are either called a paddle or a blade temple, depending on their shape.

See also: Hockey end | Paddle temple | Blade temple | Curl sides

Two hidden hinges. These are both frame front half joints with a three tenon count.

Hidden hinges

Mentioned earlier, hidden hinges avoid the requirement for traditional fastening methods such as rivets.

Instead, the two little “lugs” under the base-plate act like tree roots in the acetate frame front. Because they’re barbed, they create an undercut which makes them more stable.

Hidden hinges are only used for acetate gasses frames due to the way their inserted.

To insert the hinges, each individual hinge is rapidly heated and pushed into the acetate endpiece. The acetate melts around the lugs which creates a firm and minimal fix.

Due to the lack of rivets, hidden hinges require less space within the frame front. This makes them preferable if a designer/brand want to minimise the prominence of the endpiece.

Here’s a quick video of a hidden hinge being inserted into an acetate frame front.

See also: Hinges | Hinge graves | Spring hinges | Endpieces | Rivets

A triple-rivet hinge grave which has been freshly machined into this full rim acetate frame front.

Hinge graves

See the D-shaped recess in this acetate frame front?

Yep, that’s the hinge grave.

Sounds a little morbid but that’s where the base-plate of a hinge goes to rest before it’s permanently fastened with rivets. The purpose of the hinge grave is to make the base-plate “flush” to the surface of the acetate which makes for a sleeker, more pleasing fixture.

Furthermore, the inner walls of the hinge grave also provide lateral support for riveting which prevent the hinge from moving around as the rivets are peened.

See also: Hinges | Joint | Rivets | Rivet hole

An unpolished, tortoise acetate hockey end temple with a two rivet cluster and a visible wire core.

Hockey end

Just like a hockey stick, temples with a hockey end are curled to hook behind your ear.

In the history of eyewear, this feature is relatively modern as it only came to prominence in the 20th century. Before the introduction of drop end/ hockey end, temples were usually straight in form (paddle) or were a metal curl side.

See also: Drop end | Curl sides | Paddle temple

Joint

Another name for your glasses hinges, a fully assembled joint comprises of two half joints held together with a dowel screw.

A frame front will always contain two half joints, one on the rear-side of each endpiece. Generally, these half joints will contain fewer tenons than the half joints on the temple half joints.

For example, a 5 tenon joint means the frame-half-joint will have two tenons and on the temple there will be three tenons.

Joints/hinges use an odd number of tenons and come in different tenon-counts. These generally vary between a 3, 5, 7 and very occasionally a 9 tenon-count.

Se also: Dowel screws | Cross head screws | Hinges | Tenons | Charniers | Hinge graves

An example of a keyhole bridge in our unisex glasses model: D-TRT

Keyhole bridge

Clue’s in the title.

This style of bridge resembles that of a traditional key-hole. As you can see in the image above, the keyhole bridge emits a classic,1950’s aesthetic. This bridge-style is ubiquitous with mid-century eyewear design and production.

A simplified version of the keyhole bridge would be the less intricate “regular bridge” or as it’s sometimes called, a “saddle bridge” which resembles a simple “U” shape.

See also: Regular bridge | Bridge | Pad bridge

Close view of an 120° angled lens groove within this round tortoise acetate frame front.

Lens groove

Your lenses have to go somewhere right?

Seen above, the continuous recess within the rim of the frame front is what holds the edge of a lens in place. The angle of the cut is usually at 120° at a depth of about 1.5mm.

Together, this makes the optimum angle and depth to receive the bevelled edge of an optical lens. As the lens groove is female, and the edge of the lens is male, this union creates a reliable, repeatable connection without the requirement of screws or adhesives.

To locate the lens fully into the lens groove, the frame front is gently heated using an optical blow-heater. This makes the frame front more malleable which allows a skilled technician to slightly stretch the frame over the full edge of the lens.

In optics, this process is known as glazing and if done correctly, makes a secure and sometimes audible fit as lens “pops” into place.

As the frame cools, it contracts around the edges of the lenses thus furthering the security of the lens fit.

See also: Lenses

Loop ends

Also called a ring-end.

Located at the end of each temple, loop ends were designed like a bolt-washer to distribute the pressure of the temples on each side of the wearer’s head. They also provided a handy loop-hole for securing a leather strap to wear as a frame-chain.

See also: Curl sides | Drop end | Hockey end | Temples | Paddle temple

Pad arms

These little arms are used to add nose pads to a frame front.

As seen above, two little barbed pegs are forcefully inserted into the rear-surface of a frame front on either side of the nose aperture.

Once located, a nose pad could be attached via a very small threaded screw through the box-section of the pad arm. The box allows the nose pad to pivot slightly to accommodate the shape of your nose.

This swivel-action also reduces the need for repeated minor adjustments which may damage a pad arm from repeated bending.

See also: Nose pads | Pad bridge | Bridge | Keyhole bridge | Regular bridge

Pad bridge

Instead of using pad arms, full rim glasses frame made from acetate or horn commonly use what’s called a pad bridge.

This is where two little humps are sculpted into the frame front which rest on either side of your nose. Pads like these are extremely common in modern eyewear as they are made during the CNC machining stage of production.

Compared to pad arms, pad bridges are less likely to break as they are part of the frame itself. They can also be adjusted by reducing their height or changing their different angle with a rough file.

Once filed, the acetate or horn can then be hand polished to make each pad smooth again so it won’t rub on your nose.

To accommodate for different facial genetics, pad bridges are made to be more prominent for Asian eyewear markets. The pads tend to be much taller to make the frame more comfortable for wearers with a shallow nose.

See also: Bridge | Pad arms | Nose pads

Phillip Johnson wearing his thick rimmed architect glasses with their prominent paddle temples.

Paddle temple

Simple and straight to the point, paddle temples are uniform across their entire length and do not use a drop/hockey end.

This style of temple harks back to antiquated spectacle design where temples were considered as “grippers” instead of something that could hook behind your ear. This is because eyeglasses were worn intermittently instead of all day.

In essence, paddle temples are less refined than drop ends but they yield a very traditional aesthetic and have a certain style appeal.

In sports such as cycling or sailing, paddle temples are actually preferable as they’re less likely to interfere with safety helmet straps.

See also: Temples | Drop end | Hockey end | Curl sides

Example of a regular or “saddle” bridge on a reading glasses frame.

Regular bridge

Also called a saddle bridge, regular bridges are U-shaped and are simple and continuous in their form.

See also: Keyhole bridge | Bridge | Pad bridge

Rim

Full rim and half rim glasses frames each have a rim.

The rim can vary in thickness, but fundamentally it hosts the the lens groove and makes up the body of the frame front.

See also: Frame front | Half rim | Lens groove | Acetate

Rimless

These are the most minimal type of glades frame.

Instead of having a solid rim that surrounds each lens, rimless glasses rely on the lenses to make the majority of the frame front.

In the middle, a metal bridge is screwed onto the innermost edge of each lens. The screws pass right through the lens which make the basic frame front. At the outside edges (the endpieces) the hinges are also screwed through the lenses to complete the frame assembly.

Spectacles like these are less dominant on the face and can be very lightweight. They’re a good choice if don’t want to attract attention to your glasses but they have a habit of making you look older.

This is because they tend to lack colour and vibrancy which can make them appear somewhat impersonal and dull. If you’re looking for a more youthful glasses style, you should check out the article below.

Glasses that make you look younger

See also: Half rim | Full rim | Lenses

Side shields

Whether they’re fitted to sunglasses or spectacles, side shields have a fairly basic function. They close the gap between the edges of the frame front and your face.

For sunglasses, side shields tend to made from entirely opaque materials such as suede leather or rubber. This is to reduce sunlight from “leaking-in” from above, below or from the sides of the lenses.

This addition prevents what’s known as bounce back and also blocks debris from entering your eyes. This is why they’re popular for exposed activities such as mountaineering or riding a motorcycle.

For spectacles, side shields are generally used as a protective measure, especially in factory environments. To aid vision, they’re usually made from transparent, high impact resistant optical plastic such as Trivex or polycarbonate to let as much light-in as possible.

See also: Trivex | Polycarbonate

Spring hinges

Spring hinges are a modern adaptation of a traditional tenon hinge which reduces the need for manual adjustments.

On the temple half joint, the hinge body conceals a spring which allows the temple to extend beyond it’s maximum range of motion. This makes the glasses frame more adaptable for more head sizes as it can “spring” wider than a traditional tenon hinge.

(See image above)

Spring hinges are common amongst reader readers as they can adapt to a wide range of head sizes; a one-size-fits-all solution.

Over time, low-cost spring hinges are known to fail which renders the hinge completely loose. This failure reduces the efficacy of the temples gripping your head which usually results in the frame’s disposal.

See also: Hinges | Joint | Tenons

Supra chord

For half rim glasses, the lens is exposed in the majority of the lower half.

So in order to secure the lenses into the frame front, a female V-shaped groove is cut into the edge of the lens. This is where A Supra chord is wraps around the lens-edge which is then threaded into the frame.

By adding tension the nylon chord, the lens is pulled into the frame front which ties it into place. If you look closely at the image above, you can see the fine nylon chord and V-groove on the lens-edge.

See also: Lens groove

Tenons

On almost any glasses hinge are these little threaded loops called tenons.

They protrude upward from the base-plate of the hinge with equal sized gaps between each tenon. Each half joint of the hinge can interlock with one another via each of the tenons to create a “stack” of tenons which are secured together with a dowel screw.

Depending on the style of glasses frame, hinges can vary in tenon count from 3, 5, 7 and very occasionally a 9. The number is always odd in order to create a more stable tenon-stack.

Tenons may also be called charniers.

See also: Charniers | Hinges | Joint | Half joint | Hinge grave | Dowel screw | Cross head screw

Windsor rim

Frame fronts made from a wire rim may use an acetate beading called a Windsor rim.

This addition is made from acetate and acts like a tubular sheathe which envelopes the outer edge of the wire. The tubular, hollow acetate is very fine and has a split down its length to accommodate the frame.

Due to the vast variety of acetate colours and patterns, Windsor rims introduce colour and vibrancy to a metal wire frame. Furthermore, the acetate sheathe can be replaced if it becomes worn or damaged.

The acetate itself also acts as a protective barrier to the frame as it may be made from precious metals such as gold, silver or titanium.

Two example of wire cores for temples, one with an in-built half joint and one without. The textured finish is to hide any imperfections within the temple if it’s made from transparent acetate.

Wire cores

Wire cores are one of the more discreet parts of glasses.

Sometimes entirely hidden within the acetate, they’re used to reinforce your glasses temples to prevent them from losing their shape.

To get them into the acetate, both the metal core and the acetate temple are heated using an oven. Then, with great accuracy and speed, the core is forcefully “shot” into the hot, pliable acetate.

Once cool, the temple contracts around the wire core to create a permanent composite. The acetate remains soft, hypoallergenic and attractive whilst the core provides durable structure.

Using a machine, the temples are bent to give them a drop end. The wire core maintains this hook and prevents it from becoming deformed over time.

See also: Temples

Receive Custom Guidance

Looking for the perfect custom eyewear to represent your brand?

Reach out to Eyewearbeyond for expert guidance on choosing the best materials, styles, and customizations for your eyewear collection!